In my previous post I addressed this question in a narrow sense by responding to an E.J. Dionne Washington Post op-ed, but here I want to talk about the stimulus evidence more generally (in large part to educate myself).

A good place to start is with the report of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) who put out a quarterly report on the effects of the stimulus as part of the reporting requirement for ARRA (The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act), often referred to as “the stimulus” (though it is only one part of a larger government aid package). As of this writing, the most recent report is the Eighth Quarterly Report which is from 9 December 2011 and covers the period through the 2nd quarter of 2011 (so it is about a year old). The report is quite favorable with regard to the effects of the stimulus, perhaps not surprisingly since its three primary members (there is also a support staff) are nominated by the President.

The first item to note is that measuring the macroeconomy is hard. This should come as no surprise. The US economy is the result of the independent actions of over 300 million Americans going about their daily lives. Even at the aggregate level there are multiple state-level as well as federal fiscal policies. Sometimes these are reenforcing and sometimes competing. Additionally, there is monetary policy at the national level. Add to these the fiscal and monetary policies of other nations that affect our exports, imports, exchange rate, and capital movement. Lastly, returning to the microlevel, there are the responses to all of these factors by firms and individuals, which include their expectations about the future path and implications of these broader policies. In short, we do not know the counterfactual—what would have happened absent the policy action under examination. Ultimately, these micro and macroeconomic factors are impossible to extricate from one another so we are left only with natural experiments, history, and models.

The CEA know this truth far better than I, and they openly recognize it in the opening of their report. To compensate, they try to use as many different types of evidence as possible. The first are a few simple charts that show economic performance (GDP and unemployment) pre- and post-ARRA. Indeed, viewed graphically in these simplistic terms the economy does appear to get better after ARRA is passed (I’ve inserted an example below), though this, of course, is simply a correlation and does not necessarily imply a causal relationship.

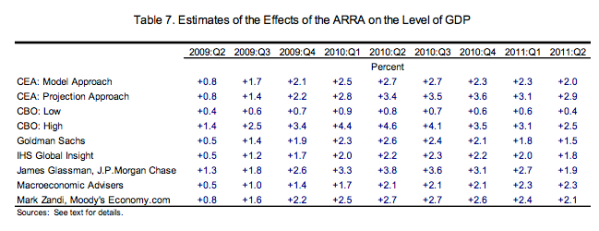

The next time of evidence is a series of economic models. This includes both a model conducted by the CEA as well as a compendium or results complied from other notable sources who used similar models.

I cannot comment on the specifics of these models as they are beyond my technical level of understanding, but I want to make a few general observations. The first is that using these models as evidence is, in a certain respect, tautological. That is to say, Keynesian-style models were used both to justify government spending through ARRA and as proof that the stimulus work. In the first case the models predicted that large increases in government spending would help increase GDP and lower unemployment. In the second case they were used to show that the aforementioned government spending increases had indeed accomplished the goal of improved GDP and unemployment figures. But they are the same models in both cases and use the same underlying assumptions. The only minor tweaks are to input the latest aggregate economic figures.

The reports, like all good social science work, make their assumptions clear, but the political and journalistic use of the reports obfuscates any of their shortcomings. Russ Roberts has gripped about this point many times. See here, here, and here, for instance. I am not making a statement here about the accuracy or usefulness of these Keynesian models, again I don’t have the technical background to do so. I am simply pointing out that to the extent that all models are inherently imprecise, they should be used accordingly by both politicians and journalists.

The third type of evidence used by the CEA report is to test the current state of the economy against statistical models using vector autoregressions (this is the mathematical technique that helped earn Christopher Sims the 2011 Nobel Prize in Economics). This method has the advantage that it doesn’t rely on a Keynesian multiplier, which is quite difficult to measure, but relies on estimations that get increasingly imprecise as the model attempts to estimate further and further into the future.

The last type of evidence is to compare the increase in the number of jobs reported by ARRA recipient organizations to a Keynesian model that has been adjusted to only include this smaller level of government spending (and exclude, for example, the tens of billions in tax breaks for individuals). Again, the report finds these figures to be in line with model predictions and thus it serves as a check that ARRA had a positive effect.

This sanguine view of ARRA has been largely echoed in the media and by particular policy oriented think tanks. But both the media and general public seem to mistake a re-running of a model with slightly updated data for delving deeply into the economy and getting more tangible figures. For instance, a 2009 NY Times article, after first describing a debate within the economics community, then declared that the fight could now be ended amicably because of new data:

These long-running arguments have flared now that the White House and Congressional leaders are talking about a new “jobs bill.” But with roughly a quarter of the stimulus money out the door after nine months, the accumulation of hard data and real-life experience has allowed more dispassionate analysts to reach a consensus that the stimulus package, messy as it is, is working.

Far from presenting hard data and real-life experience the article went on to interview a number of economists about the results of their models. But even the models aren’t all in agreement. John Taylor, for example, in his July 2010 Congressional Testimony presented results from three additional models, one from the European Central Bank, one from Robert Barro at Harvard, and one from the IMF, all of which showed limited effects from increased government spending or effects that decayed very quickly.

Even the CBO uses a Keynesian multiplier of .5 meaning that $1 in government spending increases output by only 50 cents. (Here is Valerie Ramey discussing the wide range of Keynesian multipliers that have been put forward in research papers). Taylor went on to argue that it was changes in investment, not government spending, that caused GDP to change.

In a separate testimony from February of 2011 Taylor argues that the hundreds of billions in grants to states from the federal government had little effect because states did not, in fact, increase their spending. (The counter point to this is that states were able to hang on to workers that they otherwise would have had to fire). Additionally, Taylor argues that personal consumption expenditures did not increase as a result of government tax credits. (Find all of John’s papers here).

Garett Jones and Daniel Rothschild in a pair of research papers (here and here), meanwhile, conducted the kind of hard data gathering that (I think) most Americans assume when they read the type of NY Times articles quoted above. They collected 1,300 responses from firms who received ARRA funds as well as conducted a number of interviews. They too found limited effects from the stimulus. For example, according to their survey only half of the workers hired at ARRA-recipient firms were from unemployment lines, negating much (half) of the impact of the stimulus’s primary purpose.

Another type of evidence, as I mentioned in my last post, is the Chicago Booth School’s IGM Forum. Forty of the world’s top economists were surveyed and asked about their thoughts on ARRA. While 80% agreed that ARRA had increased employment in the short-term, only 46% believed that the long-term net benefits of ARRA outweighed its costs.

Here are a couple of more papers with alternative views: one, two. There are also many more papers in favor of government spending. To me the lesson is that whether the stimulus worked depends greatly on who you ask and what evidence you prefer.